Organs are pretty great. The musical instrument, I mean. It’s pretty terrific to feel the air and earth tremble, filled with the roar of enormous pipes. They aren’t particularly nimble, of course, and volume control leaves something to be desired. But the real problem with pipe organs is their size. They don’t look well in the living room, even if you could somehow get one up the stairs.

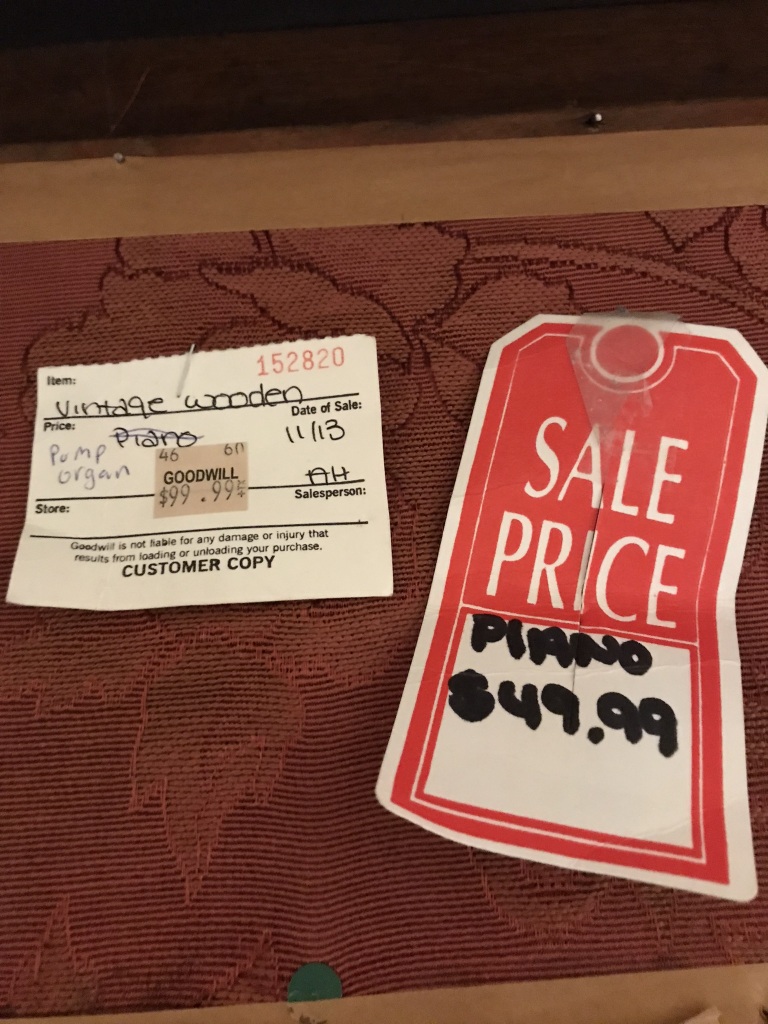

If you don’t mind losing the lower notes, though, you need a lot less room. In the late 1900s, Matthias Wandel built an awesome wooden pipe organ. It doesn’t have any stops, but it looks and sounds pretty sweet. Somewhat earlier, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, reed organs were popular. They use air pressure to vibrate a small metal reed. As a result, they can be far cheaper, smaller, and stay in tune longer than pipe organs. They don’t sound as nice as a piano, but they can be much louder and mechanically simpler. Nowadays, well-used reed organs can be found for less than a few hundred dollars1. And thus I bought one from a local Goodwill for $53.00, post tax.

My sister had seen the organ a few days earlier for $100. When she told me about it, we weren’t sure that it would still be there. But I guess reed organs are something of a white elephant. Everyone who entered the store admired it and tried to coax it into making a sound, but no one had snatched it up. When they saw that I was interested, though, they tried to convince me to buy the beauty. One gentleman assured me that it was a great investment and that, with a little work, could likely be sold for a profit2. Not that it took much persuasion. I’d never seen a reed organ before, but I wanted this one.

The organ looked pretty great, but it needed a lot of work. Superficially, it was entirely coated in a thin layer of black grime (probably coal or tobacco residue). The stops faces were fading and the keys were dirty and yellowed. The treadle board was also split in half, but that happened shortly after purchase and was mostly my fault.

More disconcertingly, the organ needed a really terrific amount of pumping to make any sound at all. I didn’t know it at the time, but a well-sealed organ should hold wind (vacuum, technically) for several minutes. Mine held wind for perhaps a quarter of a second. In addition, there were about six dead keys, and one that played a totally wrong note. I suspect the couplers were also broken, though I didn’t check properly.

On the plus side, it’s a pretty decent organ. I haven’t been able to figure out its manufacture date, but it claims to be made by the A. B. Chase Company, which means it was likely before 1900. It features two sets of reeds and treble and bass couplers, which is more than many other reed organs out there. I wish it had more than one manual (set of keys) and a sub bass, but I guess that might be more than I can chew. I’m not particularly musical but my woodworking is even worse.

Over the next few months, I plan to repair my reed organ pretty thoroughly. In fact, this blog is over a month behind. As I write this, I’ve repaired the stop action and am working on the reservoir and exhausters. I’ll probably keep posting as things progress. Hopefully someone else will find my experiences helpful, but if not, it’s fun to document these things properly.

As for programming… I’m doing more than ever… professionally. Now that I’ve graduated college and am gainfully employed, I have much less time to work on my side projects. Also, AfterZhev has been my main project for almost two years, and I have yet to find another one.

Do-it-yourself, Mr Curry

If you’re considering working on a reed organ yourself, it’s well worth spending a few hours reading about the things first. If you don’t know what you’re doing (that’s me!), it’s all too easy to damage an old organ, or make future repairs very difficult.

Rodney Jantzi’s website has been a great help to me. His restorations are mostly photographs accompanied by brief explanations, which is far more helpful and interesting than it sounds. He also has a YouTube channel where he plays his restored organs and explains some restorations.

Bill Oom’s YouTube channel has several videos documenting the actual restoration process. Probably much harder to make, but very helpful.

Reed Organ Repair - A Generic Approach by Jim Tyler is a good read. The article doesn’t contain any pictures or explain many terms (pitmans? palettes? exhausters?), though, which makes it a bit confusing. As your work progresses, though, it’ll become much more clear.

Finally, you should know that reed organ repair is smelly, time-consuming, and expensive. So far, I’ve spent over $500 on repair materials and tools. If you can amortize that over several repairs it probably becomes more reasonable, but I don’t plan to do that.

Notes

-

People try to sell them for hundred of dollars, anyway. In my uninformed opinion, unless they’re in near-perfect condition, that’s far too much. For a low-tier organ like mine, I think < $100 dollars is reasonable, especially considering the cost of transportation and repair. If you ask around, you might get one for free.

I’m guessing this makes them totally uneconomical to manufacture, even if you care more about their musical qualities than their age. So the current stock is likely all that we’ll ever get. ↩

-

Probably not, since organ repair is an expensive hobby. I doubt you can make much from reed organs unless you’re doing it for someone else or selling replacement parts. ↩